Managing Sexual Attraction in the Workplace

Since the early 1980s, KJCG has been thinking about sexual attraction in the workplace. Kaleel Jamison, our founder, published the following article, Managing Sexual Attraction in the Workplace: Intra-Staff Romances Can Damage Productivity and Morale in the magazine Personnel Administrator in August 1983. As we see more news stories about interactions in workplaces, we have been thinking about this article. While some of the language is dated, the concepts remain relevant. Sexual harassment and sexual discrimination continue to be a problem in organizations and people continue to grapple with what is appropriate in the workplace. The following article focuses on the fine line between mutual attraction and sexual harassment. Kaleel says "sexual attraction there is no component of abused power as in harassment, and no evidence of discrimination, as in sexism." Read on for Kaleel's thoughts from over 30 years ago. For a PDF version of the article, click here.

Managing Sexual Attraction in the Workplace

Intra-Staff Romances Can Damage Productivity and Morale

Sex in the workplace—especially in corporate America—is a delicate topic. It is, in fact, potentially explosive—dangerous to be involved in, dangerous to talk about, dangerous to the reputation of the corporation. Sex in the corporation can wreck careers, damage the productivity of an entire company, even affect profits.

But sexual attraction is natural. It’s normal. It happens all the time to people who work together. Some of its forms—such as sex discrimination and sexual harassment—are illegal and immoral.

But all forms of sex in the workplace carry with them the possibility of public relations problems so potentially explosive that most corporate managers would prefer not to think about them, let alone talk about them.

Most forms of sex in the workplace are not commonly thought of as important profit issues, but they are because they affect productivity. And they are because adverse public relations—or the implication that management is not entirely in control of its personnel—is always a potential profitability issue. Ask any chief executive officer who has faced a group of security analysts with a carefully crafted explanation for “what happened” in a highly public company embarrassment. Ask any financial officer who has kept an anxious eye on the stock in the wake of a company scandal.

WORK STIMULATES

Women and men do not leave their sexuality behind them when they enter the working world. It wouldn’t be healthy if they did. In fact, R. Sidenberg has pointed out in Corporate Wives—Corporate Casualties that work is sexually stimulating: “As people who have interesting careers have always known, work is very sexy, and the people with whom one working are the people who excite. A day launching a project or writing a paper or running a seminar is more likely to stimulate—intellectually and sexually— than an evening spent sharing TV or discussing the lawn problems or going over the kids’ report cards.”

Sexual attraction often occurs and goes no further. But there is always the consideration that sexual attraction may proceed—to sexual liaison or improper conduct or public embarrassment. So, like the Puritans, most business organizations prefer to pretend that the issue is not there.

The other sexual issues that occur in the workplace include sexism (or sex discrimination) and sexual harassment (another form of sex discrimination).

Sexism has been talked about for years. Not much has been done about it in many companies, but this now illegal practice is at least under discussion, and most companies are trying to amend archaic policies. Webster defines it as “the social, political, or economic discrimination of one sex by the other, specifically against women by men.”

Sexual harassment—one type of sex discrimination—has been under much scrutiny. Sexual harassment may be defined as unwelcome sexual attention that causes the recipient distress and results in an inability on the part of the recipient to function effectively in the performance of job requirements. Harassment usually includes unwanted attentions and an abuse of power, and is marked by an absence of proper respect for the integrity of another human being.

THE BIG DIFFERENCE

Far more attention has been given to both these forms of sex discrimination than to sexual attraction—though sexual attraction causes just as much organizational disruption. Sexual attraction—a situation in which one person experiences the exhilaration of inclination towards another, without the desire to diminish the other person—is different from either sex discrimination or sexual harassment. It may be disruptive, but the difference is that, properly managed, it can be not disruptive but actually energizing and productive within the organization.

Sexual attraction implies positive judgments from one or both parties. Somebody admires somebody else. Or two somebodies admire each other. With skilled management of such a situation, these positive forces can be turned to good account.

The differences between sexual attraction and the other two forms of sex in the workplace are these: in sexual attraction there is no component of abused power as in harassment, and no evidence of discrimination, as in sexism.

It is important to note, however, that sexual attraction—if not properly managed—can sometimes result in sex discrimination. Further, in the early stages, sexual harassment can be disguised as sexual attraction—until the recipient realized that there is an element of coercion in which organizational power is being abused.

This is not to say that sexual attraction is less complicated than either of the other forms of sex in the workplace. Sexual attraction can show itself along a wide range of experience—from a pleasant feeling of appreciation to falling in love. At both ends of that range, sexual attraction can be a straightforward, natural experience, and such occurrences need not—indeed cannot—be prevented in the workplace. But sexual attraction at both ends of that range can also be explosive, and a detriment to productivity if not well managed. Further, sexual attraction can produce powerful emotions that can confuse matters mightily when they occur in the workplace.

VARIED STANDARDS

An issue of sexual attraction in an organization is additionally confusing if it is viewed as taboo by the organization’s norms. In classifying cases of sexual attraction into “acceptable” and “taboo,” there is no absolute value judgment involved. But an organization certainly separates the two in its reactions, and how an occurrence is classified by an organization often determines how disruptive it may be to productivity.

A business organization is conservative—and highly judgmental. This is true no matter now progressive or freethinking its management. The organization is made up of people from different backgrounds with a variety of value systems. The net result of that potpourri of values is a conservative response to the actions of its individuals. It is as if the organization had a personality and value system of its own.

What happens to an organization making moral judgments is a matter worth an extensive analysis of its own. But it is conjectural that what happens is that sexual relationships within the organization threaten the authority relationships established by the management.

A change in those relationships—especially a change with strong emotional overtones—presents the possibility that the power hierarchy, which is dedicated to efficient productivity, will crumble. Since the structure makes the productivity possible, to strike at the authority relationships ordained by the management threatens, by implication, the financial survival of the economic entity. Whatever the underlying causes, the judgments of organizations in matters of sexual morality are inevitably conservative.

Even if an incident turns out to be “acceptable,” it is not without impact on the organization. In one organization, a high-ranking man had had a long-term relationship with a bright, able woman manager. The relationship started out as sexual attraction. It did not result in an affair. Both were married, and the relationship initially was based on simple mutual admiration. During this phase, the man took the woman’s counsel seriously and valued her judgment. They both maintained a pleasant appreciative regard for each other. Then their working positions changed, and the woman’s new job caused her to have to work more closely with the man. Almost at once, the relationship changed. The man would no longer accept her counsel. And he later went so far as to bar a promotion for her that would have made it necessary for him to work even more closely with her.

As long as the relationship had remained distant, the man could handle his sexual attraction for the woman. When the working relationship threw them into closer contact, the situation apparently suggested to him a husband/wife relationship, and he suddenly felt too vulnerable to function efficiently. The result: he failed to include her in project meetings, postponed scheduled working sessions or cut them short, and was short-tempered and abrupt with her when they worked together.

She was aware of what had happened but couldn’t seem to change the situation. She was frustrated, and that frustration diminished her excitement and interest in her job. Realizing that her progress in the company had been impeded, she eventually moved to another job in another company. From the organization’s point of view, what had been a productive working partnership was destroyed. The company also lost a highly skilled and respected woman manager.

This instance of sexual attraction was “acceptable,” by the organization’s norms of propriety. But it was not well managed, and it not only impaired productivity, it resulted in sex discrimination. What is worse, the male manager involved does not to this day understand what happened. He may again at some point be caught up in the same counterproductive pattern of behavior.

DISRUPTIVE ROMANCE

A taboo relationship, badly managed, is even more disruptive to the organization: In a large Western company, a male manager supervised a young, attractive female office manager who was his protégé. The two frequently had occasion to travel to distant cities to arrange logistics of meetings for company officials in regional operations. She was married. He was committed to another long-term relationship.

Inevitably, the affair they had carried on for some months came to light and began to be much talked about in the office, among clerical workers and professionals alike.

There was much talk and speculation about:

- Her real competence

- What impression others might have of the department

- How her advancement had affected the opportunities others who reported to both him and her

- The threat of disruptive and embarrassing emotional reactions from their respective partners.

The affair had detrimental effect on morale. The organization was angry about this affair, in spite of the fact that many of the organization’s people might, outside the workplace, have been tolerant of such an occurrence. Part of the anger was generated not by outraged morality but by a traditional feeling that the organization’s goals were being counter-productively sidetracked by a private affair.

This example illustrates a number of things. First, it shows the virtual impossibility of keeping an office affair a secret. Second, it shows that the ultimate judgment of the organization is conservative and disapproving—both for reasons of organizational morality and productivity. And finally, it shows that if an affair is taboo, involving persons who are married or attached—where there is added danger of emotional outburst—there is added stress for the organization.

No matter what form sexual attraction takes, it is potentially disruptive. Like all forms of sex, sexual attraction involves powerful emotions. That may be, in fact, why it makes many people so uneasy when it appears in the workplace, where maximum productivity is commonly thought to depend on rational behavior. Sex always carries with it a potential loss of rationality.

This uneasiness is true for someone experiencing the sexual attraction, and it is also true for someone who perceives the attraction taking place. Whether or not an initial encounter is ever carried further, the distraction takes its toll in productivity. And even if a relationship should eventually be adjudged acceptable, it diverts the energies of those who are involved and those who observe.

The organization was so upset by this liaison, in fact, that the affair came to the attention of the director of personnel, as well as the company’s president. Organizationally this situation is probably the worst sort, because it affects relationships in a single line of a department. Because of the hierarchical way in which line accountability is organized, there is a potential embarrassment for each manager in the line above, from the president on down. An organization seems able to tolerate an entanglement, even a taboo one, that goes across departmental lines better than an entanglement that breaches the reporting relationships in a single line.

PRODUCTIVITY SUFFERS

The loss to the corporation in productivity is painfully obvious, but even more startling if toted up. Several careers were damaged, perhaps irreparably. The careers of the two managers were damaged, and the work and morale of their department have suffered.

The women manager lost the authority of her position as well as her credibility, because it was the perception of those who reported to her that she was being closely directed by her love mate. She was seen as the man’s handmaiden, and her position appeared to be a superfluous level in the chain of authority. Her efficiency was also impaired, because since people no longer trusted her to maintain confidences, she did not receive information she needed to function well.

Among those in positions below hers, there was perception that the usual channels for advancement had been closed off. It became clear that she would not likely move up from her position. Because those channels were seen as closed, there was less incentive both for her and for those she supervised to perform well in order to achieve recognition and subsequent advancement.

Additionally, there are major costs and productivity losses up the line as well. In this case the president had to devote time and managerial energy to the situation. The male manager came under close scrutiny, and his managers up the line who were put on the spot are not likely to forget it. Much energy was expended both up and down the line, and the energy did not yield productive results. Clearly, when the point was reached where drastic action had to be taken, that too constituted a major disruption to the proper work of the organization.

PROPER TECHNIQUES

Everybody in business knows countless examples like these. And the only hope a manager—and a company—have of containing a problem and managing a situation so that it does not become a public embarrassment or a productivity drain for the company is to understand proper techniques for dealing with incidents of sexual attraction when they occur.

In organizations where sexual attraction is acknowledged, understood, accepted and well managed, productivity is not impaired but is in fact enhanced.

How can this be so? And what can a manager do to manage sexual attraction? Well, no manager will be successful who refuses to see the problem or who hopes that if it is ignored it will simply go away. That won’t happen.

But dealing with the problem directly is possible, and produces good results for the organization. And there is a simple technique to do it.

The theory underlying the technique is equally simple: the theory holds that intense feelings that are restrained can best be managed by a combination of verbal expression and physical action. Further, people will be more comfortable with the progress of a relationship if it proceeds through a series of interactions that take place in an appropriate sequence that gives time to build trust. When these two ideas are combined, the result is a concept that is useful for managing sexual attraction in the workplace.

The Approach Concept says that to deal with feelings of attraction, the best thing to do is to break the progression of the relationship down to a series of reality tests. The points at which a person decides to go forward or stop in the development of the relationship are already defined by social behavior patterns.

For instance, between two strangers, there is at first restraint, and a wish, generally not to violate the boundaries of the other person. When two people decide to move toward being acquainted, those boundaries will be entered. If, at each step toward friendship or intimacy, each person’s boundaries are entered only by permission, a human relationship proceeds politely and normally.

If each step comes only with mutual acceptance and tacit agreement, with the proper amount of respect on both sides, there is no sense of invasion or violation.

CONFUSED NORMS

What actually frightens some people about their initial feelings of sexual attraction, if those happen in their working world, is that these normal human emotions have surfaced in an environment w here there are no business norms to govern the progression. In a situation where the expression of such feelings is not expected, it is confusing to try to figure out whether or not it would be a good idea to fall back on social norms or to proceed on normal business norms, which require impersonal responses. The generally impersonal norms that business goes to great length to promote could be permitted to quash the feelings totally. But no matter what the people involved decide, the confusion surrounding which norms to use has already been enough to throw them both off center, to distract them, and to impair their focus on the job at hand.

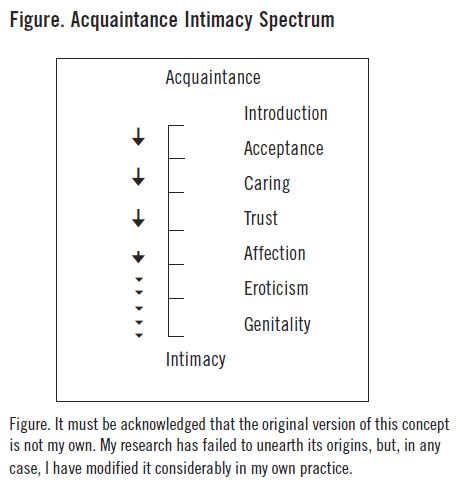

The progress from acquaintance to intimacy operates, in stages, along a spectrum (see Figure below).

After an initial meeting, the first stage is acceptance. So, after a verbal greeting, society—business society too—sanctions a first level of touch, the handshake. The second point is caring. This can show up in another kind of touch—like a casual assistance, help up a step, or help with a heavy door or a package. The third point is trust. This point might show itself in touch in a casual, accidental way. Brushing against somebody (not with sexual motive, but in truly accidental fashion), without embarrassment or undue confusion, bespeaks trust that the encounter was, in fact, accidental and not worth remarking.

The fourth point is affection. This might show itself in a casual hand on the shoulder or an arm around the shoulder—again without sexual intent. Up to this point, both the stages and the encounters are perfectly appropriate for a business organization. The fifth point, however, is eroticism. Touch at this stage is touch designed to give and receive pleasure. It is explicitly sexual in nature, and clear permission has to be granted before this point is reached in a relationship. The sixth and final point is sexual foreplay and geniality, resulting in sexual intercourse. Clearly, most business relationships do not usually, and should not, get beyond the fourth point—affection.

People are confused and feel violated only if the sequence in the development of a relationship is either rushed or taken out of order. But it is reassuring to know that any relationship needs to go only as far as the person who wants it to go least far decides.

And it is possible for a manager to help people to see that the existence of these choices at every stage in a relationship allows them to manage the sexual attraction they may feel—or the sexual overtures they may receive.

SELECTING A STRATEGY

How a manager handles an occurrence of sexual attraction should be determined by a number of factors—whether the attraction has caused any overt behavior, whether a relationship has developed, whether that is taboo or acceptable by the organization’s values, whether the people involved are handling the situation discreetly themselves, and how much talk and disruption the attraction may be causing the rest of the organization.

Approaching the problem is thought by most managers to be the toughest part: it is difficult to talk about emotional situations and people may be embarrassed and disposed to deny that anything at all is happening.

If it’s a matter of simple sexual attraction that has not yet been acted upon, a casual mention of what the manager has observed—made separately to each party—may lead to a talk about the awkwardness. The manager should mention in a private, but gentle way, that the manager has noticed an uneasy working relationship. If the person denies that there is a problem, the manager might simply say: “Don’t discount the possibility of sexual attraction. When two attractive, competent people work together, that often happens and isn’t immediately recognizable for what it is. Sometimes it shows up as conflict in the relationship, or an inability to be articulate, or a self-consciousness never noticed before.”

Encourage both parties to consider attraction as a possibility, and help them to see it as positive. Attraction is, after all, a compliment. They can— never fear—manage it. It doesn’t have to get out of bounds. It helps to understand what is happening. Then, if both parties are sophisticated, they might even be able to discuss the matter, celebrate the compliment to each other, and dispel the tension. If they can’t talk about it to each other, at least having an understanding, savvy confidant helps them to deal with the matter.

When the woman in a situation like this is the lower ranking of the two parties—and she frequently is—she may bring the subject up with her manager voluntarily, because she may be puzzled by a change in the relationship and think that her performance is in doubt. The manager who is sensitive enough to see what has happened can help her to deal straightforwardly and appropriately with what has happened so that she is clear about what her behavior should be to avoid difficulties.

THE ACTIVE AFFAIR

If matters have escalated already, and there is a growing relationship underway, the manager’s role must be human and supportive, but firm about addressing what is affecting the organization and the productivity of the workers.

Again, the manager should approach each person separately—first, the higher ranking of the two parties, on the theory that the major responsibility is always lodged there. Tell the person that there is a need to talk about a situation that could be disrupting the organization. Make clear that there is no intention of imposing any value judgments on what has happened. In any such situation, the manager needs to be able to analyze and describe clearly:

- The effect of the organization—projects are behind schedule; mistakes are being made; energy and productivity are low because organizational energy is going into speculation about this issue.

- How careers will be affected—decisions on salaries, promotions, task force assignments, and career mobility will be skewed by the presence of romantic feelings. A person can’t properly supervise others where there is a romantic involvement with someone in the direct management line.

The manager must be able to offer assistance as a clarifier and consultant to both principals as they sort out their own values and make choices. The manager must emphasize that the two principals must work out the matter for themselves after they consider the consequences.

And the manager should be able to talk candidly, and empathetically and listen in a receptive and non-judgmental way.

Even with these skills, and given a manager comfortable with the process, the number of possible reactions from the principals is great, and the kind of response is unpredictable. Most people, however, will be having doubts and confusions about their situation. Most will find it a relief to talk about the problem. And most will be grateful to have limitations they know they must deal with. There is something soothing and reassuring about knowing that, however out of bounds one feels, there are safeguards to keep conduct appropriate.

A SYSTEMATIC ISSUE

Usually, even the people involved can see that sexual attraction is—however much their own business—also a systemic issue. An affair is a secret. The more forbidden its character—by the values of the essentially conservative organization—the more seductive it becomes as a focus of attention. The more focus the secret, forbidden issue attracts, the less energy and attention there is for the business of the business. There is no implication that

the secret should be broadcast to the entire organization. But if a manager is willing to be candid, and non-judgmental in the handling of the situation, that style, in itself, goes far to diminish the secrecy and excitement and drama of the situation so that the organization can get on with its business.

The least damage will be caused by defusing sexual attraction early. And a relationship that the organization views as acceptable according to organizational values need not be disruptive if the manager’s handling of it is straightforward.

The most damage is likely to be caused by a relationship that is taboo. That is because the organization’s values are for predictability, professionalism, reason and productivity. The greater the potential disruption and embarrassment surrounding the relationship, the more anxiety and “illicit” actions are likely to produce. A manager who handles a situation tactfully without stress to the organization reassures the people in the organization of the competence and skill in leadership.